The last few days I’ve been hunting a bug in a C++ project I’ve been working on. This hunt again showed me how easily you can break C++ programs by accident (something that isn’t possibly in Java or C#). You need to completely understand the inner workings of C++ to avoid such pitfalls.

The whole problem was a result of me thinking that C++ references (&) are just pointers (*) that have some restrictions (e.g. they can’t be NULL). Wrong! What’s even worse: They’re sometimes just pointers with some restriction. This makes them work in some cases but fail in others.

Let me take you on my journey and you’ll hopefully avoid this (very subtle) mistake in your work.

The Basic Idea

Let’s examine the basic (and partially constructed) idea. Say, you have two classes, BaseClass and its child ChildClass:

class BaseClass { };

class ChildClass : public BaseClass { };

Furthermore, say we have a pointer to an instance of ChildClass called g_somePointer.

// Exists as long as the program runs.

// NOTE: This is stored as a BaseClass pointer.

BaseClass* g_somePointer = new ChildClass();

Now imagine, you want to write a wrapper class around another class providing you with a reference to this pointer g_somePointer. Let’s reduce the code to the function returning the reference (called getReference()) and the function wrapping it (called getReferenceWrapper()):

typedef BaseClass* BaseClassPointer;

const BaseClassPointer& getReference() {

// now "ref" is just another name for "g_somePointer"

const BaseClassPointer& ref = g_somePointer;

return ref;

}

const BaseClassPointer& getReferenceWrapper() {

const BaseClassPointer& ref = getReference();

return ref;

}

The last thing is some testing code which simply calls the wrapper function and does something with the returned pointer:

void main() {

const BaseClassPointer& ref = getReferenceWrapper();

ref->doSomething();

}

Executing this code will work as intended (but only tested with Visual C++ 2010 and g++ 4.6.1). ref in main() will “contain” the address to the ChildClass instance - the same as stored in g_somePointer.

Two Little Changes Turn the World Upside Down

Now, for some reason you want to change the variable type of g_somePointer from BaseClass* to ChildClass*:

// Exists as long as the program runs.

ChildClass* g_somePointer = new ChildClass();

The program will compile fine (even with the highest compiler warning level) and running the program will - at least with the compilers mentioned above - work as intended.

Let’s introduce a second - as it seems - totally unrelated change to the implementation of getReferenceWrapper(), adding a new local variable:

#include <string>

...

const BaseClassPointer& getReferenceWrapper() {

std::string someString = "ignore me"; // <-- this is new

const BaseClassPointer& ref = getReference();

return ref;

}

This shouldn’t have any impact on the program, should it?

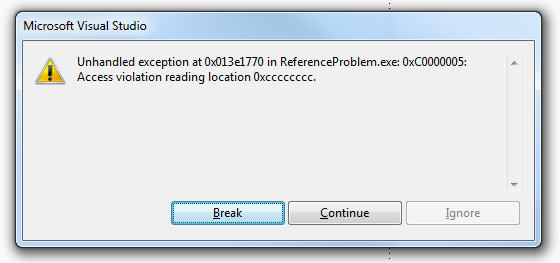

With me asking this question you probably already know the answer. Executing the program now should give you a segmentation fault/access violation.

A segmentation fault

A segmentation fault

What has happened? This second change seemed totally unrelated. Let’s debug the program. I’ll only show the relevant code and mark the current execution position with an arrow:

const BaseClassPointer& getReferenceWrapper() {

std::string someString = "ignore me";

const BaseClassPointer& ref = getReference();

return ref; // <---

}

At this line (return ref;) ref still contains the correct address.

const BaseClassPointer& getReferenceWrapper() {

std::string someString = "ignore me";

const BaseClassPointer& ref = getReference();

return ref;

} // <---

At this line, the content of ref suddenly has changed to some invalid garbage. “What’s going on here?” you might ask.

The Cause

It may have looked like nothing but the actual cause for the problem was changing the data type of g_somePointer to ChildClass*. Let’s explore this.

First, the current implementation of getReference() is hiding the problem from the compiler. That’s why it can’t issue a warning (and neither Visual C++ nor g++ will).

const BaseClassPointer& getReference() {

const BaseClassPointer& ref = g_somePointer;

return ref;

}

Let’s change this implementation to an equivalent (and more simple) one:

const BaseClassPointer& getReference() {

return g_somePointer;

}

Now the compiler will give you a warning:

- Visual C++: warning C4172: returning address of local variable or temporary

- g++: warning: returning reference to temporary [enabled by default]

Important: Don’t be as stupid as I was and try to “fix” the warning by using my initial implementation of getReference(). This warning is there for a reason and the reason is not that the compiler is too dumb to figure out what to do.

The compiler is telling you here that you’re returning a reference to a local variable. This is always a bad thing. The questions now are:

- Why is this a bad thing?

- Where does the local variable or temporary (variable) come from?

You won’t get this warning if you change the data type of g_somePointer back to BaseClass*. So, under some conditions the current implementation of getReference() is actually valid.

Why is this a bad thing? (Stack Frames)

If you already know why returning a reference to a local variable is a bad thing (or if you just accept this fact), skip this section. If not, read on.

The problem here is that local variables reside on the so called “stack” (or “call stack”). This is a continuous section of memory that grows with each function that is called (and also shrinks again once the function returns). The following image shows the call stack for a function (= subroutine) named DrawLine(), called from a function named DrawSquare():

Layout of a call stack (source: Wikipedia)

As you can see, there are two stack frames here (blue and green) - on for each function. Each stack frame contains the “Locals” (i.e. the local variables, such as “ref”) of the associated function. The stack frame (and with it the locals) of DrawLine() (the callee) is stored above the locals of DrawSquare() (the caller). Currently the function DrawLine() is being executed, indicated by the position of the “Stack Pointer”. When DrawLine() returns, the stack pointer will move to the top of DrawSquare()’s stack frame (the blue section). When this happens the stack frame of DrawLine() (the green section) will become invalid. Invalid here means that the memory section previously occupied by the stack frame (green section) must not be used anymore. If DrawSquare() now calls another function, this new function’s stack frame will replace the content in the green section with its own content.

Now, if you have a reference (or a pointer for that matter) to a local variable of DrawLine(), this reference will “point” to some content that’s no longer available. And that’s bad. The values of these references will change just by calling a function that doesn’t even know these references. On the other hand, if you don’t call another function, your code may work (just like our example code above did before introducing the local variable someString) and hide the problem. Small code changes or turning on code optimizations (like when switching from debug to release build) may (or may not) surface the problem again. This kind of problem is a real pain, as you can imagine.

Where does the local variable or temporary (variable) come from?

Back to the warning. We’re being told by the compiler that we’re returning a temporary (i.e. a “variable” automatically created by the compiler). Where does this temporary come from?

Remember that the warning doesn’t appear when g_somePointer has the type BaseClass* (but it does appear if it has the data type ChildClass*). Here’s what the compiler basically converts the new implementation of getReference() into (I’ve actually extended the code a little bit to better show the problem):

BaseClass* g_somePointer;

const BaseClassPointer& getReference() {

// temporary is just another name for g_somePointer

BaseClassPointer& temporary = g_somePointer;

return temporary;

}

Now, when you change g_somePointer’s data type to ChildClass*, the compiler will convert the implementation into something slightly different:

ChildClass* g_somePointer;

const BaseClassPointer& getReference() {

// The "static_cast" isn't technically needed here.

// It's just here to show that a cast is done here.

BaseClass* localPointer = static_cast<BaseClass*>(g_somePointer);

// temporary now is another name for localPointer (and no longer for g_somePointer)

BaseClassPointer& temporary = localPointer;

return temporary;

}

Here the compiler creates a local variable containing the pointer to the base class of ChildClass. This is required because in C++ the pointer to a base class doesn’t necessarily have to have the same address as the pointer to a child class. This is especially true when the child class inherits from multiple base classes. See this example:

class BaseClass1 { };

class BaseClass2 { };

class ChildClass : public BaseClass1, public BaseClass2 { };

ChildClass* ptr = new ChildClass();

BaseClass2* basePtr = ptr;

// now possibly: "basePtr != ptr"

Because of this address change the compiler can’t just use g_somePointer for temporary. It needs to cast the instance first and then store it in some variable (here: localPointer). It than creates the reference to this local variable, which is bad as explained in the previous section.

Adding the local variable someString to getReferenceWrapper() broke the code above because std::string is a class that has a destructor. The destructor is “just” a method (function) which is automatically called when the object (someString) goes out of scope. As I explained in the previous section, calling a function overwrites the call stack above the current function’s stack frame (i.e. the green part in the image above), thereby overwriting the memory section containing the address to the base class of g_somePointer (to which our reference pointed).

Working Example

I’ve attached the whole code of the example so that you can try it out for yourself.

Summary

Returning a reference to a pointer will result in “unpredictable” (or at least undefined) behavior when the reference’s type is a base type of the pointer’s data type.

The following code will work (although you might consider it fragile)…

BaseClass* g_somePointer = ...

typedef BaseClass* BaseClassPointer;

const BaseClassPointer& getRef() {

return g_somePointer; // works

}

… whereas the following code won’t (i.e. results in unpredictable behavior). Note that just the data type of g_somePointer changed to ChildClass*:

ChildClass* g_somePointer = ... // <-- different

typedef BaseClass* BaseClassPointer;

const BaseClassPointer& getRef() {

return g_somePointer; // illegal - introduces local variable

}

This code is illegal because the compiler needs introduce a temporary, local variable in getRef() to store the resulting address of the (static) cast from ChildClass* to BaseClass*. And then the function returns a reference to this local variable instead of a reference to g_somePointer.